Designer Spotlight: Albert Hadley

“Flair is a primitive kind of style. It is innate and cannot be taught. It can be polished and refined. When a person has flair, a grounding in the principle of design, and self-discipline, that person has the potential of being an outstanding designer.” – Albert Hadley

Design school has taught us all to worship the techniques of revolutionary designers of our times such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies Van Der Rohe, and more modern heroes of Sir David Adjaye, Zaha Hadid, and Peter Zumthor. Maximalism was never encouraged or used as examples by my teachers; you can feel their distaste of too busy or “unclean design.” Maybe, it’s of an era gone by and viewed as antiquated, represented in medieval Catholic cathedrals with its stained glass and relics, or observed in a civic rotunda with an intricate painted or mosaic-tiled ceiling. For this reason, we are repeatedly given reference to and taught of “modern” creators who use seamless lines, simple palettes, and profound moves.

As a Southerner & Tennessean, this architectural education goes against everything I was taught. I hoarded books that illustrated unimaginable worlds and seashells from eighteen years of vacations and countless participation trophies and kitschy souvenirs from landmarks across the United States. My childhood room is a patchwork square to a larger quilt of my home; from an outsider’s perspective, it is not a “clean” place. It is tidy but is bursting at the seams with characterizations of three children raised in a home and a nearly thirty-year marriage. It is decorated in a thrifty admiration of antiques with appreciation of texture and color and admonishment of clean lines; give my mother a dovetailed drawer or give her death.

It was maybe my second or third year of architecture school when I went to lunch with my grandmother, mother, and BettyAnn, my grandfather’s cousin. It was on the way up there that Mama explained that I may be particularly interested in BettyAnn, as her apartment was decorated and designed by her brother, Albert. I’d only heard of Albert in passing and Papa never mentioned his cousin much except that he was an excellent illustrator and a bit of a curiosity. Unlike most of the Hadley family, Albert lived somewhere outside of the Tennessee borders so he was an even stranger enigma to me and my siblings.

Upon entering BettyAnn’s apartment in Nashville, I was transported into a classical and vibrant compact space. The floors were patchwork patterns of black and white checkerboard to a more detailed diamond pattern. The sitting room was to the left, just past a narrow kitchen with bright cabinets and dinette table; the sitting room was populated with high-backed plush chairs within walls of mint paint, framed botanical drawings of various plants or butterflies, endless bookshelves filled with books with warm-toned hardbacks.

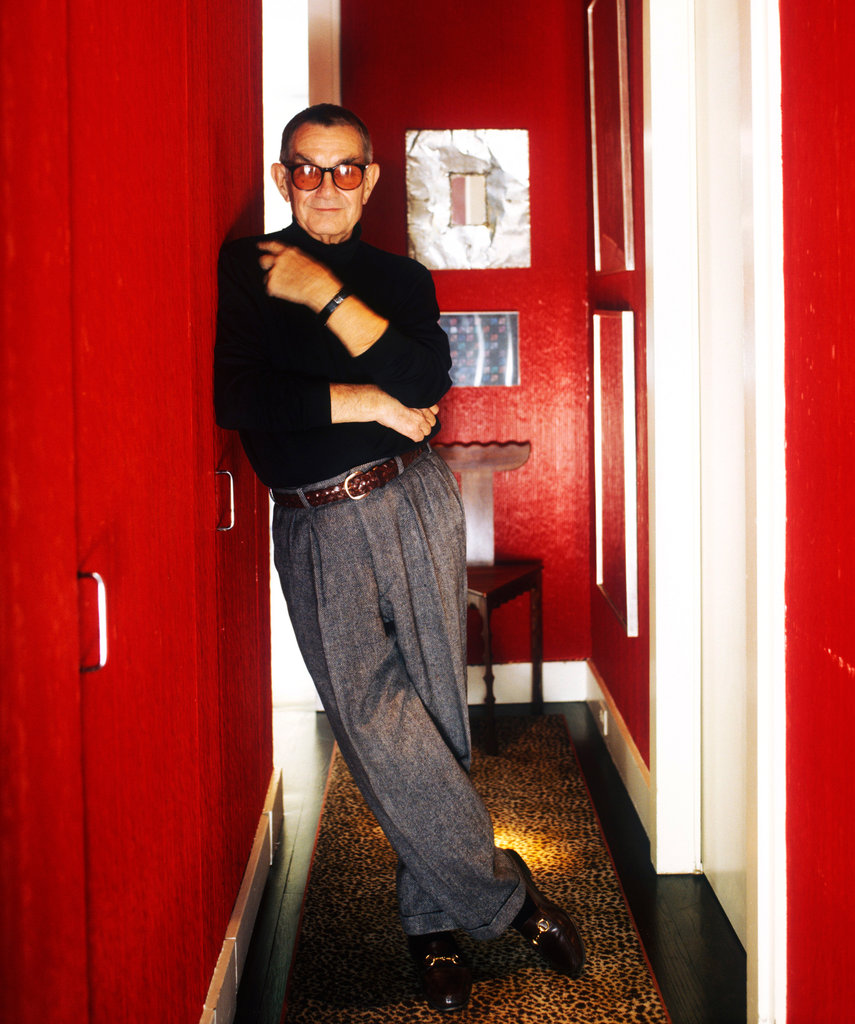

To enter this place was to take a tour in Albert’s mind; walls were covered with his original sketches and artifacts from their childhood. BettyAnn pointed out a stunning landscape their mother composed, indicating that Albert’s talents were beyond just his own legacy. Further in, we discovered a black porcelain bathroom, a closet curated into a personal sewing room with built-ins for material storage and projects, and various other petite rooms with specific delicacy and southern mementos in a composed manner. Each room used wallpaper that suited the personality of that space; some were a bright pink with white floral linework and an even more intricate style of miniscule red clover on a white background.

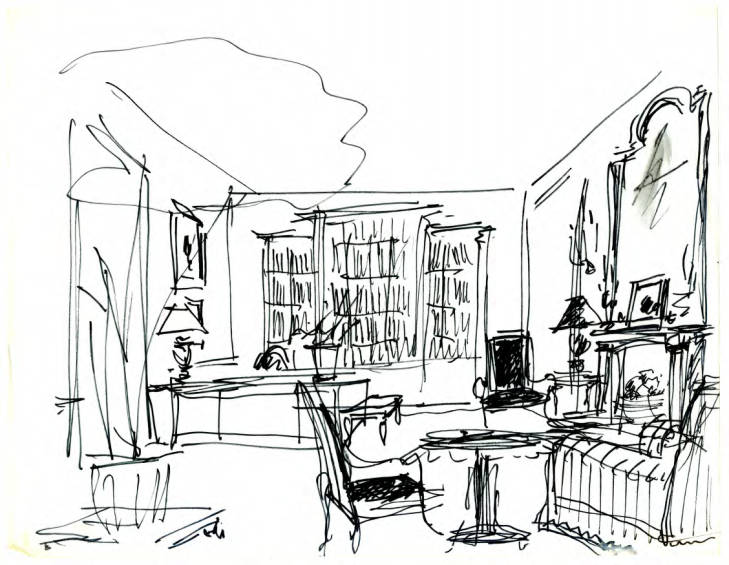

This small apartment in West End was so curated to BettyAnn’s lifestyle and personality, a resounding affirmation of a designer’s talents when the space reflects the client. I instantly loved it and returned home to look at the Paris-Hadley design book that has been sitting in our living room unsuspectingly and found designs that were intricate and layered, as if a modern retelling of the opulence of a French king matched with the eclecticism of a fifth-generation Tennessean.

Yet, we do not have many designers that rely on opulence and maximalism as a design choice. It’s unpopular and when stumbled across, a novelty. I had the opportunity to visit The Graduate Hotel in Knoxville, TN and immediately saw how Albert’s legacy continues. In this hotel (and presumably all Graduate hotels) the visitor experienced layered artifacts with plush style and vibrant environments. In fact, this place was like a museum of Tennessee football with delicate ads from the 1920s and supersized Sports Illustrated covers of Tennessee legends paired with velvet green couches and rattan chairs and neon signage and an orange & white chevron floor. How can minds can marry seemingly opposite and clashing materials and make it work and create a rich experience?

Opulence, vibrance, and maximalism are bold design decisions. Its application makes the experience all the more memorable and enchanting as it usually is exposing the personality of the client. I encourage you to seek out and experience maximalist spaces and appreciate each detail – you know the designer has selected everything down to the picture frame.

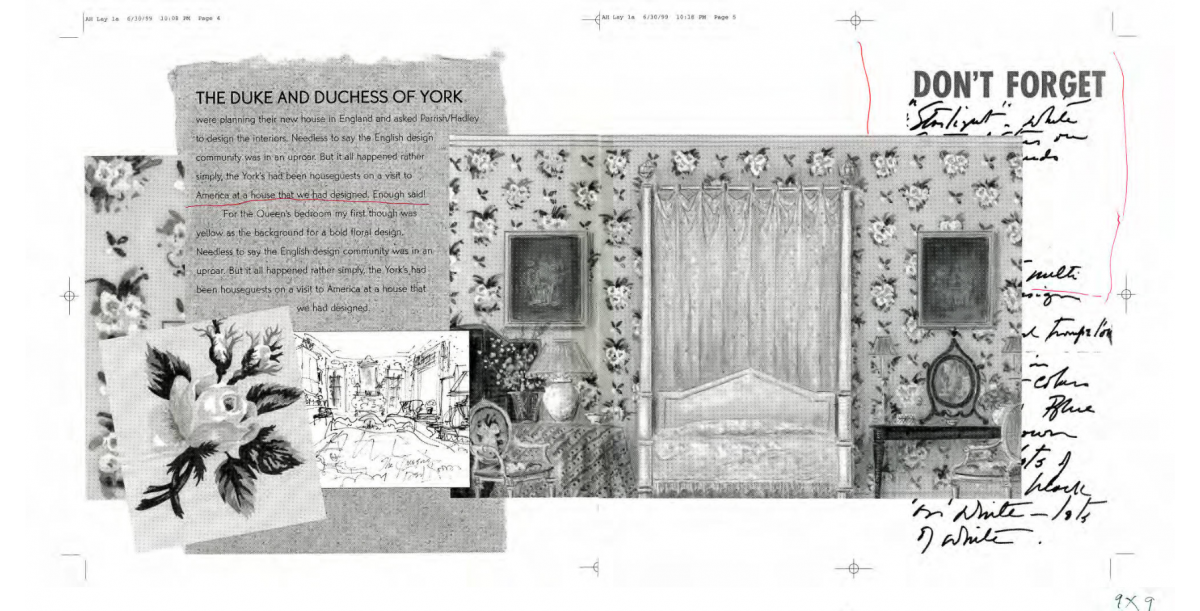

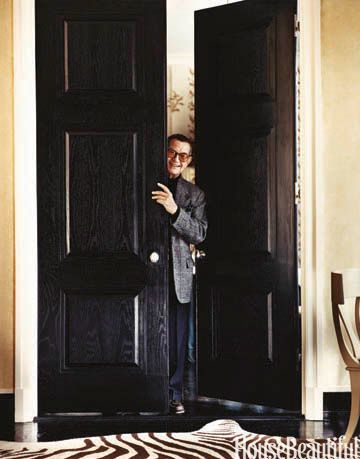

Albert had the honor of designing for the likes of Vice President Albert Gore & family, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Diane Sawyer, the Astor and Getty families and from rumors in the family tree, he was close to designing for the royal family in England. How did a Springfield country boy turn into a significant influence to the world of design? I’m still trying to figure that out with every family interview and piece of correspondence and rough sketch that I come across.

For more information on this curious designer, I suggest you look into the Tennessee Archives for his sketch collection as well as the occasional exhibits they rotate in the Nashville Library of the donated materials. Furthermore, Parish-Hadley has many publications and articles on their work.