Preserving the Harlem Sky

The architectural discipline is accompanied by many rich sub-genres which can be expanded upon infinitely. Urban design, sustainable design, and historic preservation are just a few of the disciplines that inform, act in dialogue, and respond to architectural design. In my own explorations, I’ve found preservation to be a practice that most encapsulates the potential of all these disciplines to work in support of one another, and I have spent the past year completing the first half of a master’s in Historic Preservation at Columbia University. The following text captures the conclusion of my final studio project for spring 2022. Set in Harlem, this proposal seeks to bridge the dialogue between historic urban fabrics, energy, and equity by means of preserving the Harlem Sky.

Source: Shutterstock

The practice of preservation is entangled with many super-environmental forces which, together, can perpetuate or dismantle systemic injustices. This proposal, entitled “The Harlem Sky: Viewsheds and Energy Open-Scapes” seeks to reconcile the relationship between preservation, energy, development, and economic justice through the implementation of a solar district.

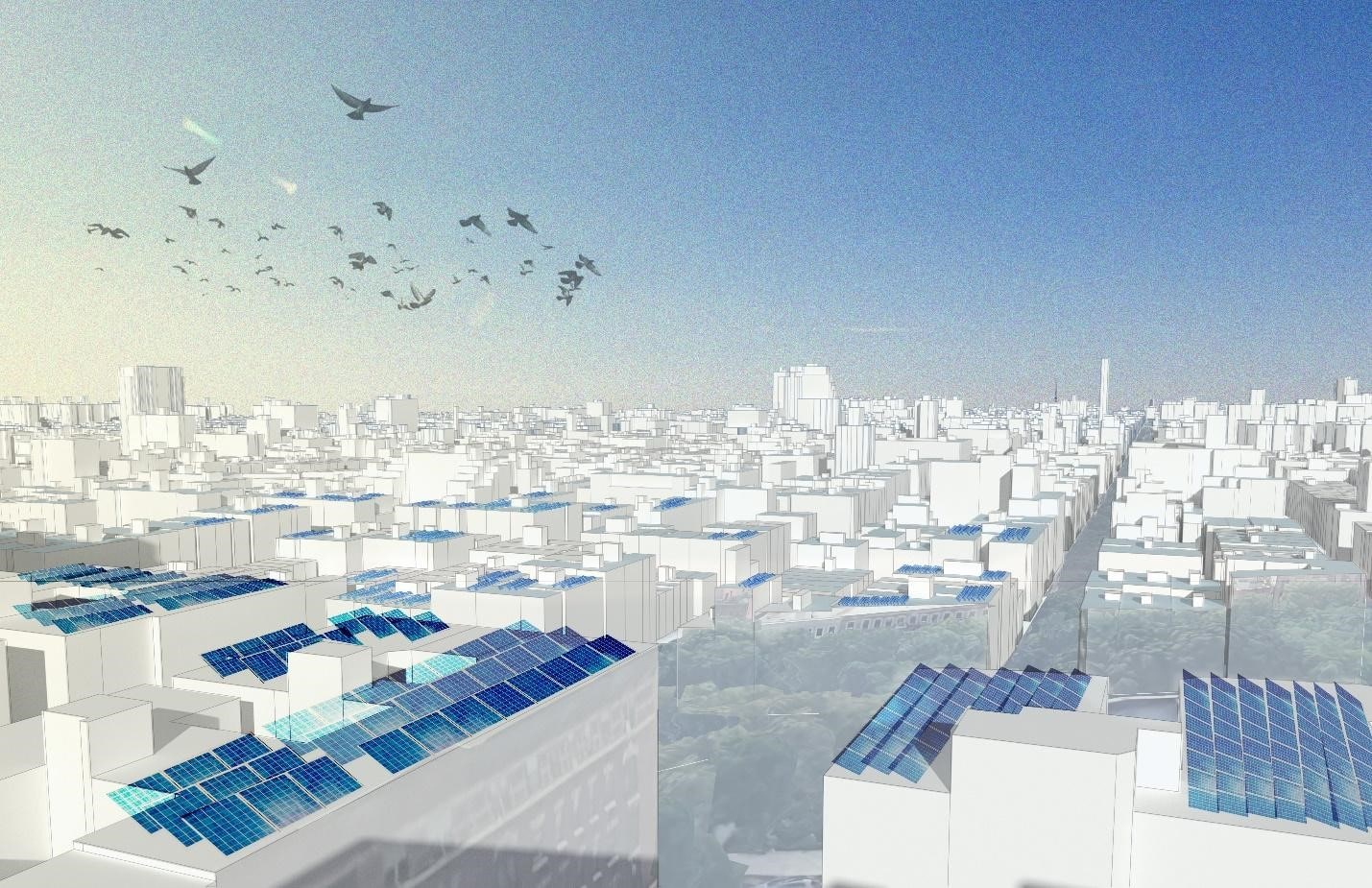

During an interview with a Harlem Community board member, the Harlem sky was cited as an asset and key characteristic of the Harlem community. The sky is an open-space asset for the Harlem community, with tangential connections to other characteristics such as building heights, population density, fresh air, and one’s personal access to open space. Building height, in particular, has a clear relationship to one’s access to the sky, as the height of a building can limit one’s access to the open space from the ground. Considering the average building height in Harlem is 19’ below the Manhattan average, one’s access to the sky, including daylighting and heat, is characteristically greater in Harlem. This diagram illustrates generalized building heights throughout Manhattan, though does not account for topographical differences. Further analysis of the streetscapes in Harlem, Midtown and Soho seek to illustrate typical conditions of building height and street wall to better understand what characterizes access to the sky in each neighborhood.

Creator(s): Schuyler Daniel

Data Source: CARTO

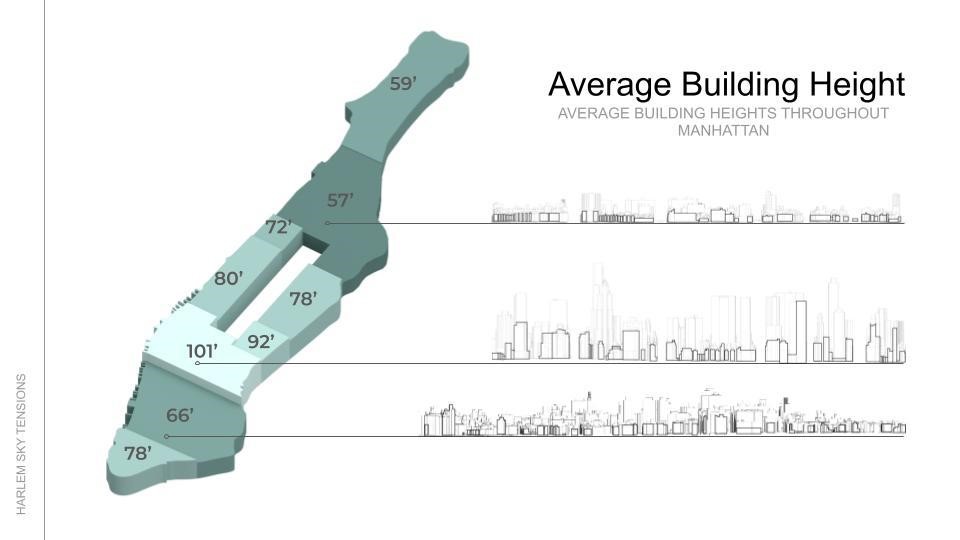

Lower building height, while providing access to the sky as an open space resource, is also associated with other environmental factors such as daylighting, shadow, and heat. These diagrams illustrate shadows over 6th and 7th Avenues in both Harlem and midtown at three times throughout the day. While more daylight reaches the street in Harlem than in midtown, this area of Harlem also experiences average temperatures 2-3 degrees higher than the Manhattan average. Here, air-related conflicts playing out. Building height correlates to more street in shadow, while more street daylighting also raises average outdoor temperatures, placing higher demands on energy for cooling.

Creator(s): New York City Council Data Operations Unit

Data Source: New York City Council Data Operations Unit https://council.nyc.gov/data/heat/

Composed by: Schuyler Daniel and Ziming Wang

The GIF above shows available FAR additions in shades of blue and historic sites and districts in shades of black. Those properties shown in the darkest shades of blue are assumed to be at a highest risk of redevelopment due to the value of their unused FAR allowances. This map will be used to inform a pilot solar district.

Composed by: Schuyler Daniel

Image Elements: NYC Planning, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission

Composed by: Schuyler Daniel

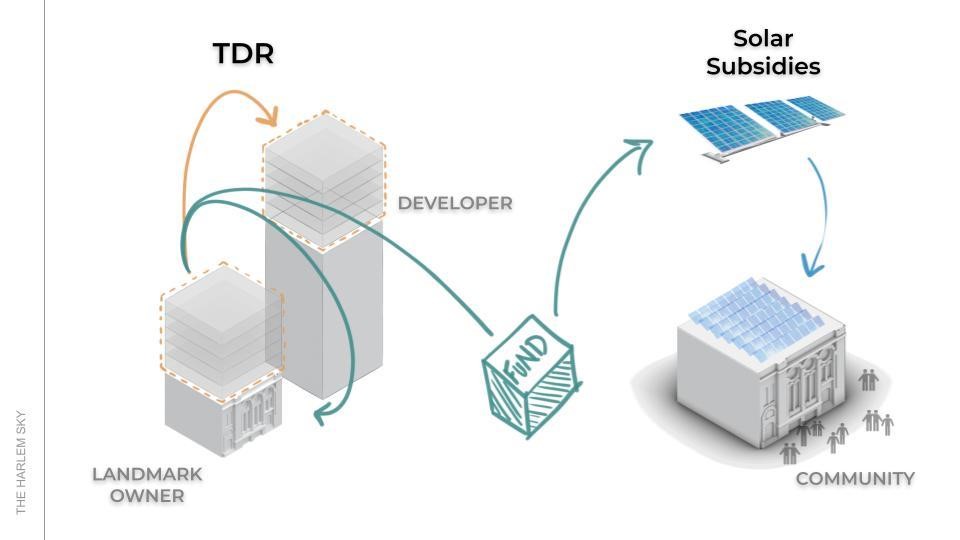

This proposal utilizes Transferable Development Rights, or TDRs, as a mechanism by which to offer economic agency to individual building owners in the preservation of the existing low-rise building stock of Harlem. In essence, TDRs allow a building with existing air rights the opportunity to sell their air rights to be allocated elsewhere. Thus, the height this building owner had access to can be sold and added to another project’s air rights (NYC Department of City Planning 2015). As building owners choose to sell their air rights to developers outside of a designated district, a percent of the sale would go into a fund accessible to other owners within the low-rise district for the purchase and energy retrofit of solar panels for buildings within a designated receiving district.

In essence, this system benefits three parties: “The owner of a designated landmark building can realize an economic gain by selling their unbuilt, but allowable, development rights; the buyer of these rights, in return, can acquire additional floor area they would otherwise not have; the neighborhood, meanwhile, can retain an the amenity of a revitalized landmark” (NYC Department of City Planning 2015). This proposal also aligns with WE ACT’s initiative launched in 2016 called “Community Power,” which identified “the need for energy independence as a priority in Northern Manhattan, and specifically for alternatives to the fossil fuel power being offered by existing utilities” (WE ACT 2016).

Image Elements: NYC Planning

Composed by: Schuyler Daniel

This proposal suggests the implementation of a Pilot Solar District within the area of the Mount Morris Park Historic District and Extension. Landmarked buildings and districts have a standing history of using TDRs as a mechanism of preservation, where landmark “owners would sell unused development rights to “adjacent” properties, which include “contiguous” properties plus those directly across the street or that share an intersection (NYC Department of City Planning 2015). Transfer could also happen at potentially greater distances. This location capitalizes on existing landmark regulation and seeks to promote energy transition in landmarked areas. While a designated receiving district or zone is not specified here, potential sites could include properties adjacent to the Historic District along corridors such as Adam Clayton Powell Blvd or across greater distances to 2nd or 3rd Avenues.

Composed by: Schuyler Daniel

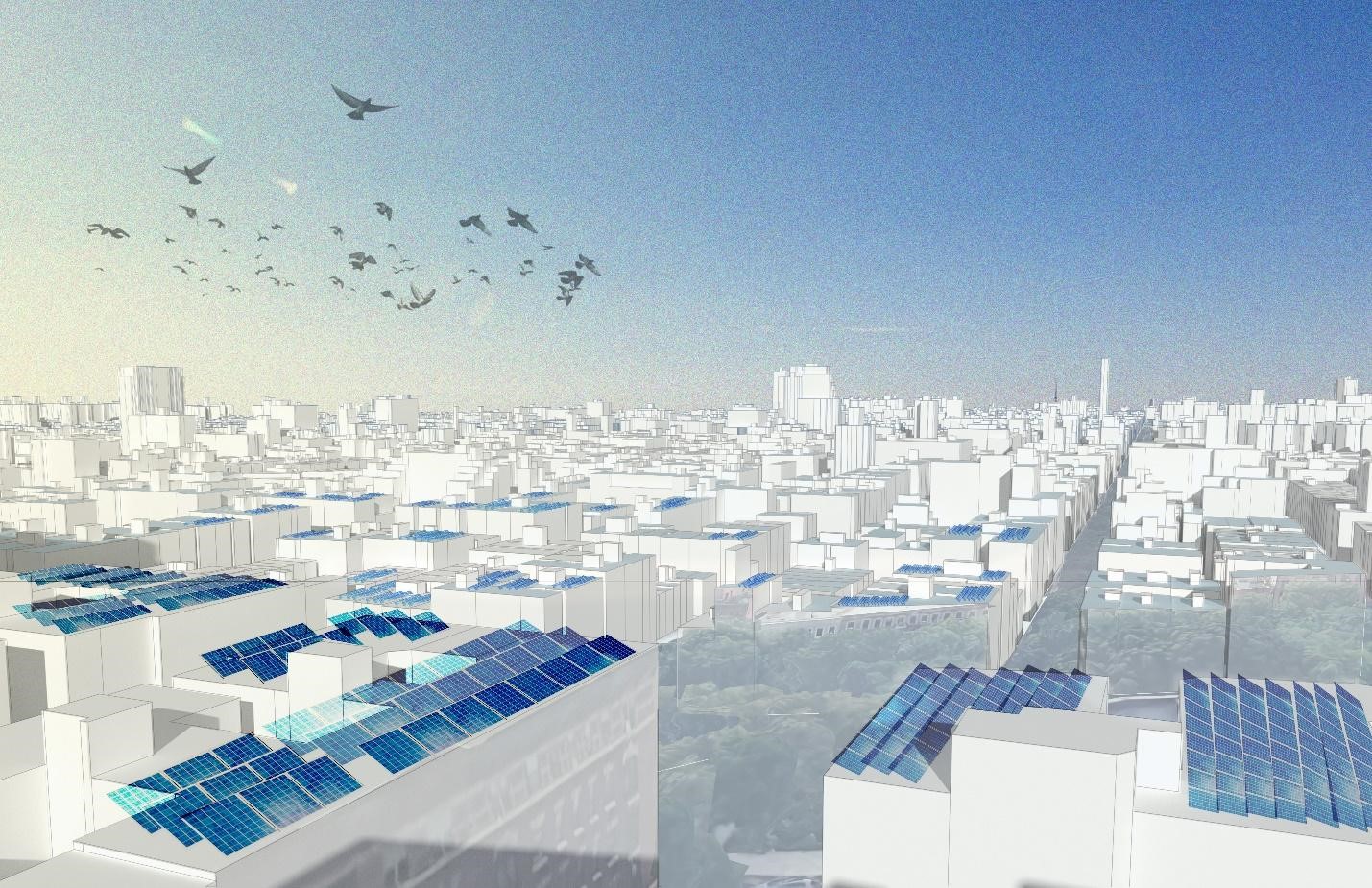

This solar district acts in simultaneous support of the preservation of Harlem’s historic assets, such as the open sky and characteristically shorter building stock, while harnessing the unobstructed sunlight reaching the tops of buildings. While many historic structures and districts qualify for exemption of updated energy codes, this proposal recognizes preservation’s responsibility to respond to New York’s 2019 Climate Mobilization Act, specifically requiring all new construction to have either green roofs or solar panels. Ultimately, the solar district open-scape has three goals: distribution of economic agency through TDRs, improving access to renewable energy, and historic preservation both on the ground and in the sky.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

WE ACT. “Community Power: A Community Solar Project in East Harlem.” WE ACT for Environmental Justice. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.weact.org/campaigns/community-power-a-community-solar-project-in-east-harlem/.

Sherpa, Shaky. “Estimated Total Annual Building Energy Consumption at the Block and Lot Level for New York City.” Sustainable Engineering Lab, Columbia University, & Spatial Distribution Of Urban Building Energy Consumption By End Use. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://qsel.columbia.edu/nycenergy/.

Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize. “Innovative Zoning Tools — West Chelsea & High Line Plan.” Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www.leekuanyewworldcityprize.gov.sg/resources/case-studies/west-chelsea-high-line-plan/.

Lumen Now. “How Much Power (Watts) Does a Solar Panel Produce?” March 4, 2021. https://lumennow.org/how-much-power-does-a-solar-panel-produce/.

NYC Department of Planning. “Transferable Development Rights – DCP.” Accessed May 3, 2022. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/planning/plans/transferable-development-rights/transferable-development-rights.page.