Transgressive Urbanism

At the time of my fifth year, I had not done much theoretical design work. Simultaneously, my interest in all types of crime had reached an all-time high thanks to the sensationalism of podcast journalism and Netflix documentaries. This meant that thesis was the time for me to explore the relationships of criminal and unusual uses of architecture.

My precedents were not only criminals but films – To Catch a Thief; The Sting; Ocean’s Eleven; Inside Man; Baby Driver. Each depicts a different type of crime in a different era illustrating various methods of using space. I also diagrammed historic crimes such as the famed cat burglar Bill Mason and his phenomenal feats of climbing towering residential buildings or the robbery of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Other times I studied strange urban phenomena such as a false townhome front in Manhattan that is used as ventilation for the subway or the hidden underground entrance to the Waldorf Astoria Hotel used by presidents.

You might be surprised to find that there is a vast amount of literature on the criminal use of architecture. If you haven’t read The Burglar’s Guide to the City by Geoff Manaugh, it must be on your bedside table stack soon.

“In one sense, burglars seem to understand architecture better than the rest of us. They misuse it, pass through it, and ignore any limitations a building tries to impose. Burglars don’t need doors; they’ll punch holes through walls or slice down through ceilings instead. Burglars unpeel a building from the inside out to hide inside the drywall (or underneath the floorboards, or up in the trusses of an unlit crawl space). They are masters of architectural origami, demonstrating skills the rest of us only wish we had dark wizards of cities and buildings, unlimited by laws that hold the rest of us in.”

– Geoff Manaugh, A Burglar’s Guide to the City page 13

Manaugh revealed a language that I was struggling with wording – do we really use our buildings to their most potential? Are criminals the only group of individuals who have maximalized the use of the built environment?

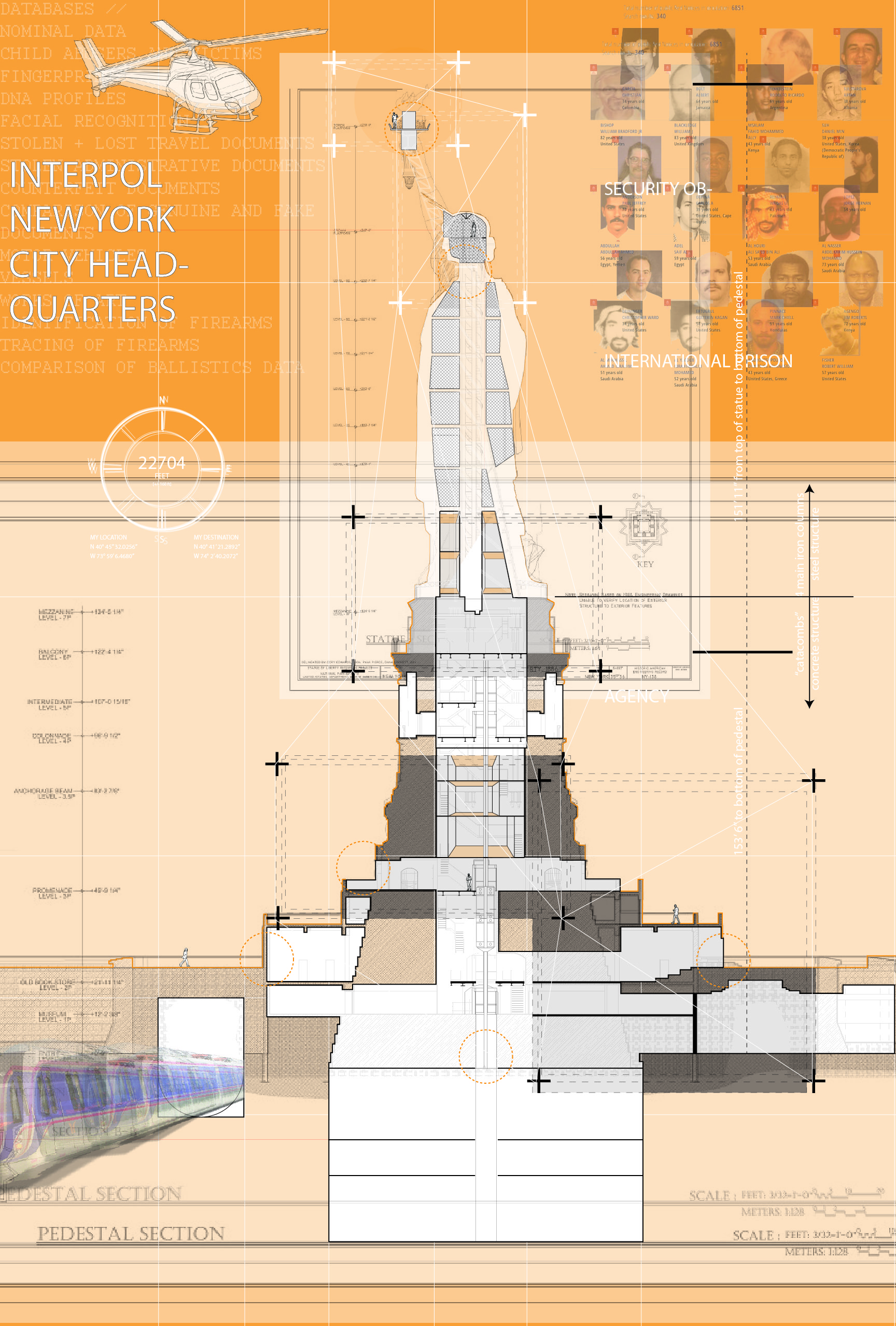

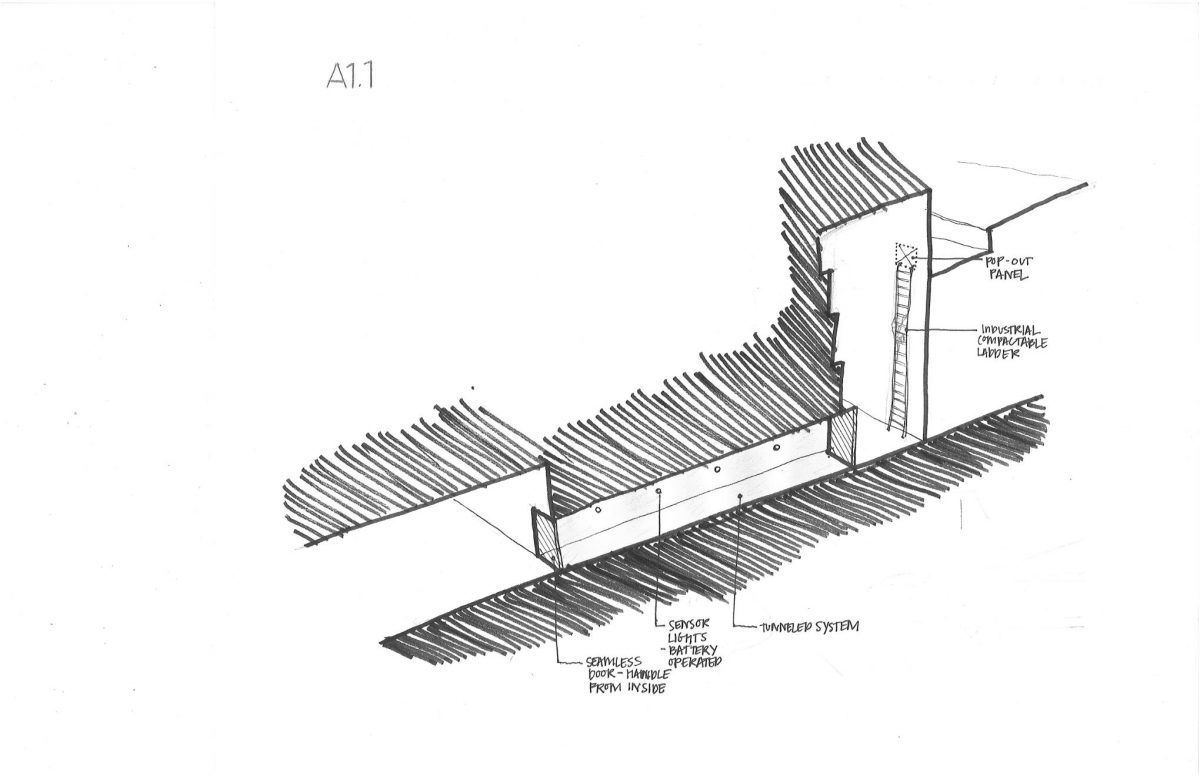

A criminal or person seeking to misuse space has a certain talent for envisioning space in transgressive methods. They visualize their targets in section or axonometric in order to understand how spaces relate to each other to create the necessary environment needed. They recognize latency, a condition in which the density of the urban environment provides pockets of spaces that are sought out for activities that are not socially accepted. They are talented in existing under-the-radar, operating without others noticing.

Trespassers know the best facades for climbing. Con Artists know the best environments for taking advantage of the naive. Burglars know the best ways to infer the layout of a space, to calculate the most productive means of accomplishing a goal. Smugglers know the best methods of moving illegal products over borders.

My thesis was a study of the unseen city of New York City and exposing the database of latency typologies within its urban fabric by means of investigating elements of spatial misappropriation, surveillance, camouflage, and perception by way of the criminal lens. I was interested in crime that used space i.e. covert agencies, black markets, squatters, heists, secret societies, etc.

I conducted three studies. First, I looked at their path, the equipment, the relationships, the escape, and what is done with the object afterwards. Second, I trained myself to think like a criminal with identifying targets, settings, companions, means of entry through a series of fictional crimes and storyboarding. Finally, identify examples of criminal activities and architecture in New York City to develop the context of the “unseen city”. The last exercise included expanded examinations of the Flatiron Building, abandoned subway tunnels, Times Square, and the Statue of Liberty.

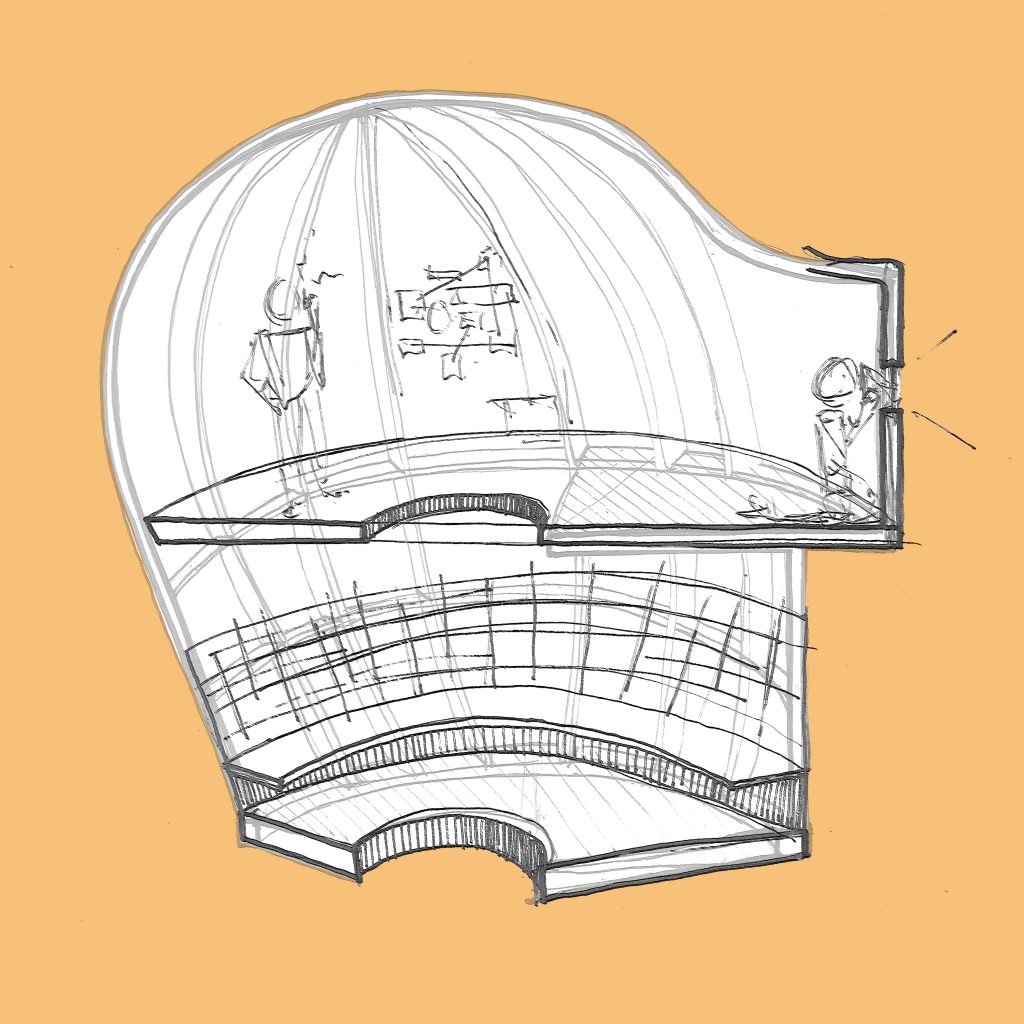

Center Image: depicts sketch of Manhattan surveillance room

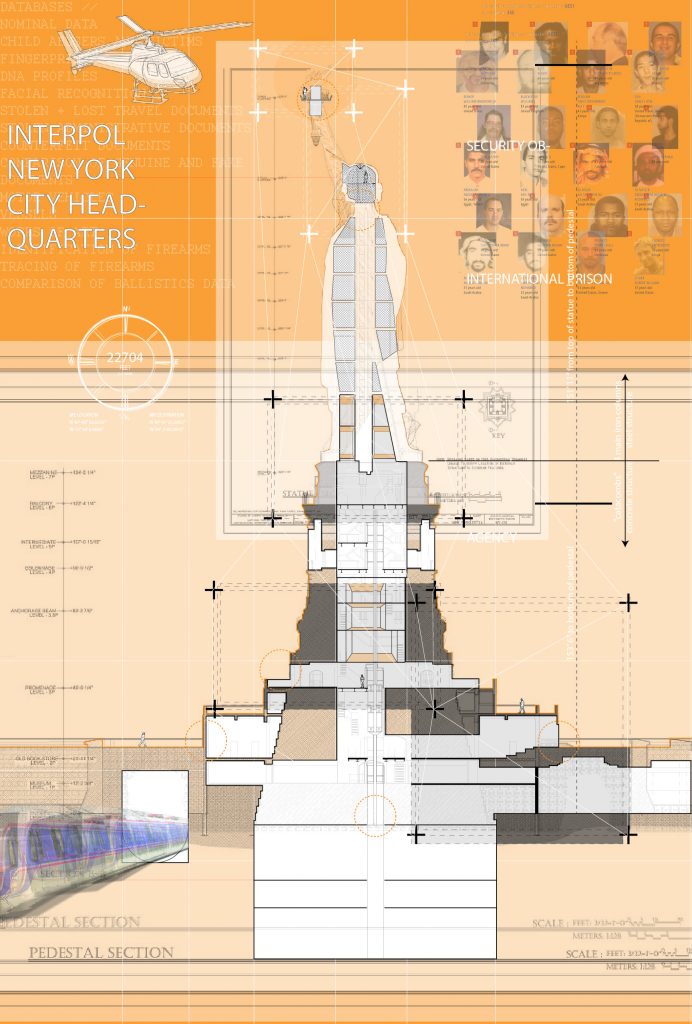

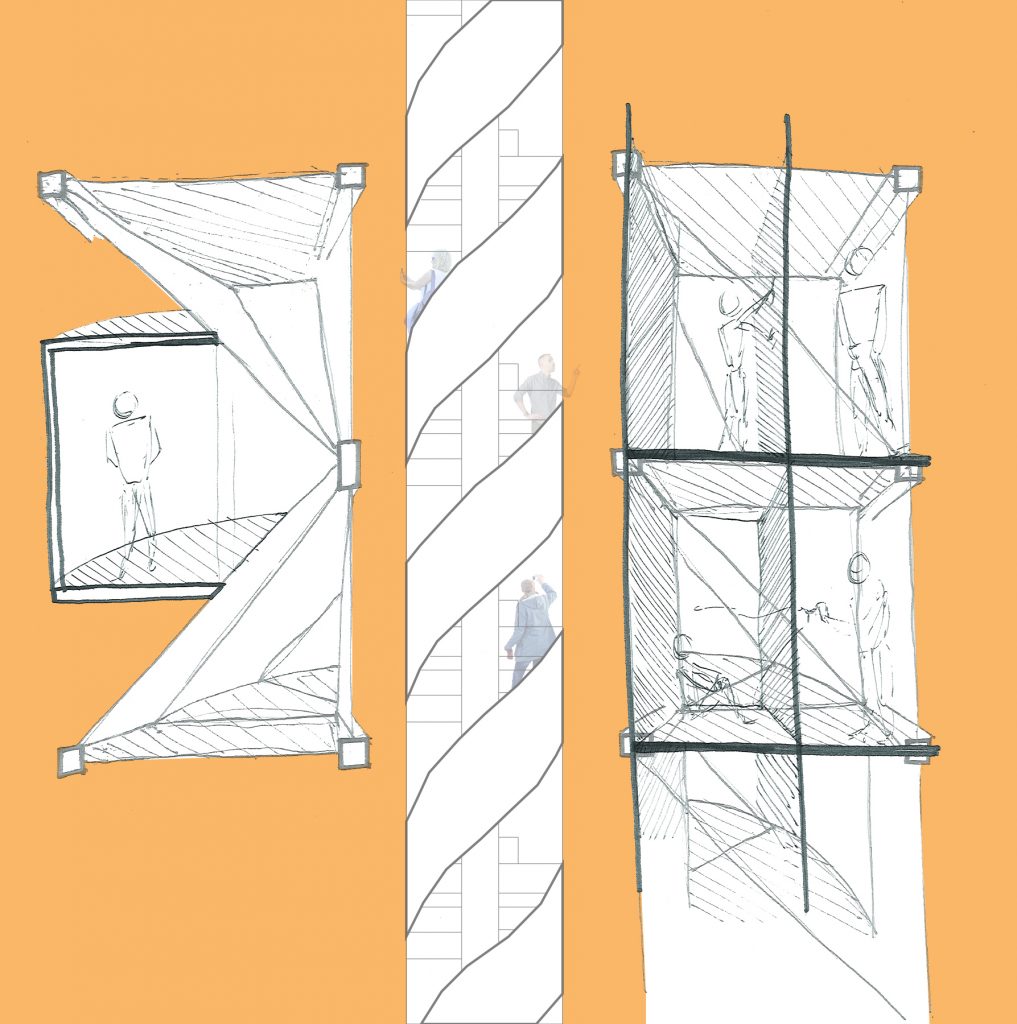

Right image: juxtaposition of tourism through the body of the statue with holding cells for international criminals

The Statue of the Liberty is the true icon of New York City, a piece that has welcomed immigrants for years and a popular site for Americans. New York City is an international city, and thus, draws in people from all types of paths, including criminals. Parts of the Statue were closed post-9/11, despite having numerous accessible avenues to explore Lady Liberty. The Statue hosts examples of latent structure: the body has steel beams and columns to support the curvature of the form while the base is monolithic stone that is carved away for designated spaces. This proposal imagines taking advantage of the latency by infilling the web-like structure with transparent volumes and carving away at the stone base to create new rooms for new programs. In this case, the imagined occupant would be an American-based Interpol International Headquarters; this was to address the changing types of criminals in New York City as well as understand how public space could be taken advantage of in an unseen way.

The base would be carved away for the more mundane, office-type headquarters. The body would be transformed into a holding cell space for convicts that is interjected with a visitor’s museum. The head will be a space for surveillance of Manhattan from afar, in conjunction to the torch, whose purpose is undisclosed. Perhaps for one of the most elite leaders in Interpol or maybe a high-security cell or maybe a laboratory of sorts. Below is a private subway station that will follow the line to other sites in the unseen city. The visitors who visit inside the Statue will not be blinded from the activities happening. In fact, this conjunction of programs desires juxtaposition.

This is only one of many sites in the unseen city in the Big Apple. If you want to hear more, you know where to find me. In the meantime, read Geoff Manaugh and keep your eye out for abnormalities in our southern urban city.