Adaptive Reuse and the Authenticity of Place

Renovations change a building. Restorations lock a building in time. Adaptive reuse carries its story forward. Every preserved beam, brick, and window tells a chapter of a building’s history, reminding us of the people and purposes that once shaped a place. These tangible elements become symbols of memory and identity, anchoring a community in it’s past while guiding it toward a more sustainable future.

Adaptive reuse has become a growing part of Nashville’s DNA, and Smith Gee Studio (SGS) has helped write that story. From Werthan Warehouse and Cummins Station to the revitalized 13-acre Neuhoff District and the Gulch, our team has been behind some of the city’s most cherished transformations. Founding Partner Hunter Gee, Partner Jesse Wilmoth, and Senior Project Managers Omar Bakeer and Kara Gee share lessons from reimagining the city’s industrial past, reflecting on how listening to buildings, respecting their character, and embracing the unexpected have shaped our approach to adaptive reuse.

Listening to the Building

At Smith Gee Studio, we approach adaptive reuse as an act of listening. Every building has a story to tell through its structure, history, and limitations; our role is to interpret that story. Beyond technical feasibility, successful adaptive reuse is built on understanding a project’s sense of place within its neighborhood and the role it has played in the lives of those who came before.

That listening begins with a series of early questions: Could the building add value to the site and neighborhood? Is the core sound enough to support a new life? Will saving it enrich the user experience? Aligning these early assessments with a client’s vision and expectations is a critical step before design begins.

From there, the process often leads to what our team calls “anti-design.” Anti-design is not about opposition but about restraint and intentionality. Knowing when to intervene and when to let a place’s story lead the way is as much a design decision as creating something new. At Neuhoff, even the demolition contractor became part of this process, carefully pausing mid-work to ask when to stop demolition and what to preserve.

Listening to the building is, above all, a collaborative process. It requires integrated teamwork, with architects, engineers, contractors, and trades all working together to find solutions that honor the past while adding future value within the constraints of a project.

Neuhoff Curve Building, Photography by Christopher Payne

Expect the Unexpected

Adaptive reuse is as much about discovery as it is about design. Beneath every surface lies the potential for surprise; navigating those surprises requires patience, creativity, and resilience. Unforeseen conditions emerge at every stage, warranting adaptability from clients, contractors, and design teams. As Hunter Gee often reminds us, “Expect the unexpected. There are always surprises.”

Those surprises often stem from the existing fabric of the building. Low floor-to-floor heights, outdated systems, or hidden structural weaknesses can quickly alter the course of a project. Kara Gee recalls how uncovering old ceilings often forces a complete reevaluation of HVAC and electrical integration. “Everybody wants the cool old beams and brick, but that means you cannot just run wires across the ceiling. You have to think about every move and work with what is there.”

Other times, surprises come not from what is missing, but from what is revealed. Historic finishes, artifacts, or structural elements uncovered during demolition can shift priorities, sparking new conversations about what to preserve and how to adapt design strategies around those discoveries. These moments often add both complexity and authenticity, reminding us that adaptive reuse is as much about responsiveness as it is about vision.

The unexpected is not simply an obstacle to overcome but a defining aspect of the process. Each challenge becomes an opportunity to rethink assumptions, refine details, and find creative solutions that allow the past and present to coexist within the same space.

Cummins Station Community Garden, Photography by Matthew Carbone

Sustainable by Design

Adaptive reuse is one of the most direct ways architects can practice sustainable design. As often said, the greenest building is the one already built. By working with what exists, we reduce waste, avoid sending material to the landfill, and eliminate the energy and emissions required to extract, process, manufacture, and transport new steel, concrete, or brick. Omar Bakeer explains, “The life cycle of a building is resource-intensive. Saving the structure is the most sustainable thing you can do.”

Older buildings also carry lessons for modern sustainability. Many were designed long before the introduction of mechanical systems, yet they perform remarkably well. Thick masonry walls regulate temperature, operable windows provide cross-ventilation, and thoughtful siting strategies leverage shade and natural airflow. “There is a lot to learn from older construction,” observes Kara Gee. “They were built to last and often more responsive to the climate than the way we build today.”

Sustainability also means respecting craftsmanship. At Cummins Station, massive timbers and masonry were restored rather than replaced. At Werthan Warehouse, the original brick was carefully repointed and steel windows restored. Each decision avoided waste while strengthening authenticity, turning what might have been discarded into an opportunity to tell a story. True sustainability preserves both resources and meaning, allowing buildings to carry their value forward for generations

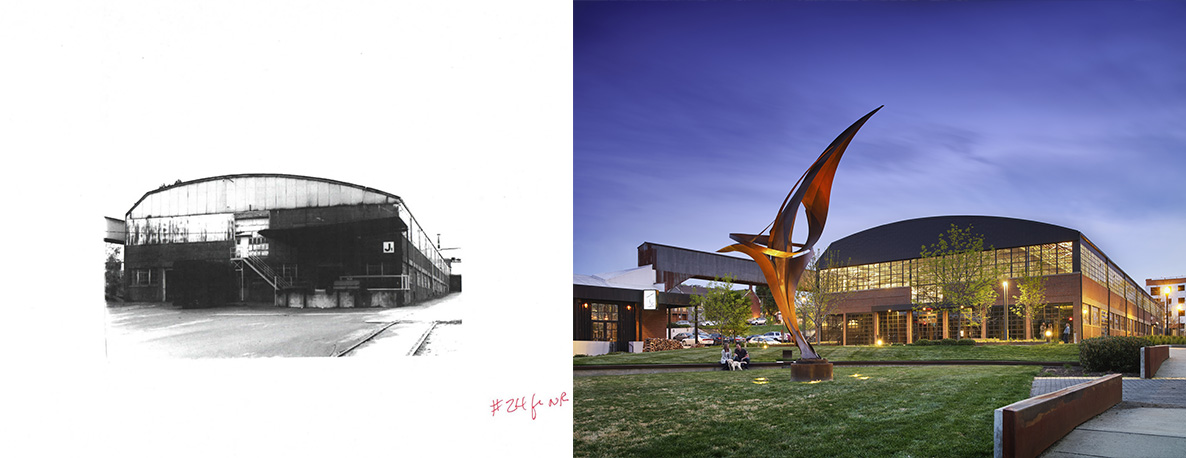

Werthan Warehouse, Before and After, Photography by Matthew Carbone

Balancing Old and New

Every adaptive reuse project involves choices about what to preserve and what to reimagine. Some elements prove invaluable, while others cannot be justified. Successful projects strike a balance where modern functionality and historic character meet, honoring the past while creating spaces that resonate with today’s clients and communities.

As Hunter Gee explains, each component requires careful evaluation: what is worth salvaging, what is not, and where the tipping point lies. Those decisions often shift depending on ownership goals. For a client planning to hold a building for decades, investing in energy-efficient systems and salvaged materials makes sense. For an owner intending to sell in only a few years, the equation changes. The architect’s role is to guide clients through these trade-offs while ensuring the essence of the building remains intact.

Integrating modern systems while allowing history to remain visible demands precision and restraint. Knowing when to add, when to subtract, and when to let the existing structure speak for itself is the true craft of adaptive reuse.

Every Building Tells a Story

Every building holds a story shaped by its neighborhood, its history, and the lives of those who came before. Preserving that story is just as important as preserving the structure itself. As Omar Bakeer reflects, “It’s not just bricks and mortar, it’s the cultural and social context of the building, neighborhood, even the city, that gives adaptive reuse its real value.”

That context is what ties people to a place. Neighbors recognize what stood before and value when improvements build on that story rather than erase it. This perspective shifts the role of the architect from preserving materials to shaping meaning. Reuse is not preservation for its own sake. As Jesse Wilmoth cautions, “sometimes what endures is not the physical structure but the story or idea it represents.” Understanding those stories before making design decisions is just as critical as analyzing the building itself.

In this way, adaptive reuse becomes an act of storytelling. By weaving the remnants of the past with the needs of the present, architects create spaces that resonate with cultural memory while remaining relevant for today and the future. What is saved and what is transformed often carries significance far beyond the building itself, extending to the identity of a neighborhood and even a city.

Adaptive reuse is not only a way to preserve the stories of the past but also a catalyst for future narratives. For more than a century, the expansive Werthan Packaging property stood as a barrier between two neighborhoods. Through selective demolition of unstable structures and the introduction of intentional pedestrian connections, the site has been transformed into a permeable landscape—one that invites movement, fosters community connections, and offers a new way to experience these historically significant relics.

Designing for the Next 100 Years

Preserved structures anchor neighborhoods in memory while opening doors to the future. They give texture to city blocks otherwise dominated by new construction and help ensure that new development feels authentic rather than mass-produced.

As Hunter Gee reflects, “We could have demolished everything in the Gulch, but it wouldn’t be as rich of a place. Even non-descript one-story brick warehouses now live to tell the Gulch’s railroad distribution past. Authenticity comes from knowing something was here before and continuing that story.” In other cases, preserving elements like Music Row studios or churches carries profound emotional weight for communities, even when the buildings themselves lack architectural grandeur. These stories and touchstones matter deeply to people’s sense of belonging.

At Smith Gee Studio, we view adaptive reuse as both a responsibility and a privilege. It challenges architects to practice restraint, embrace collaboration, and imagine how history can inspire future generations. As Kara Gee observes, “If a building has lasted 100 years, you are not just preserving the past. You are setting the tone for what survives the next century.”

Adaptive reuse is not the resistance to change but the careful design of it. Whether it means preserving a warehouse, reimagining a transit station, or transforming a district, each choice extends the story of a place while creating the foundation for stories yet to come. Designing for the next 100 years means honoring what already exists while building with quality and longevity in mind. The greenest building may be the one already built, but the most meaningful ones are those that continue to evolve, sustaining both memory and use for generations to come.

Top Photo: © New City Properties